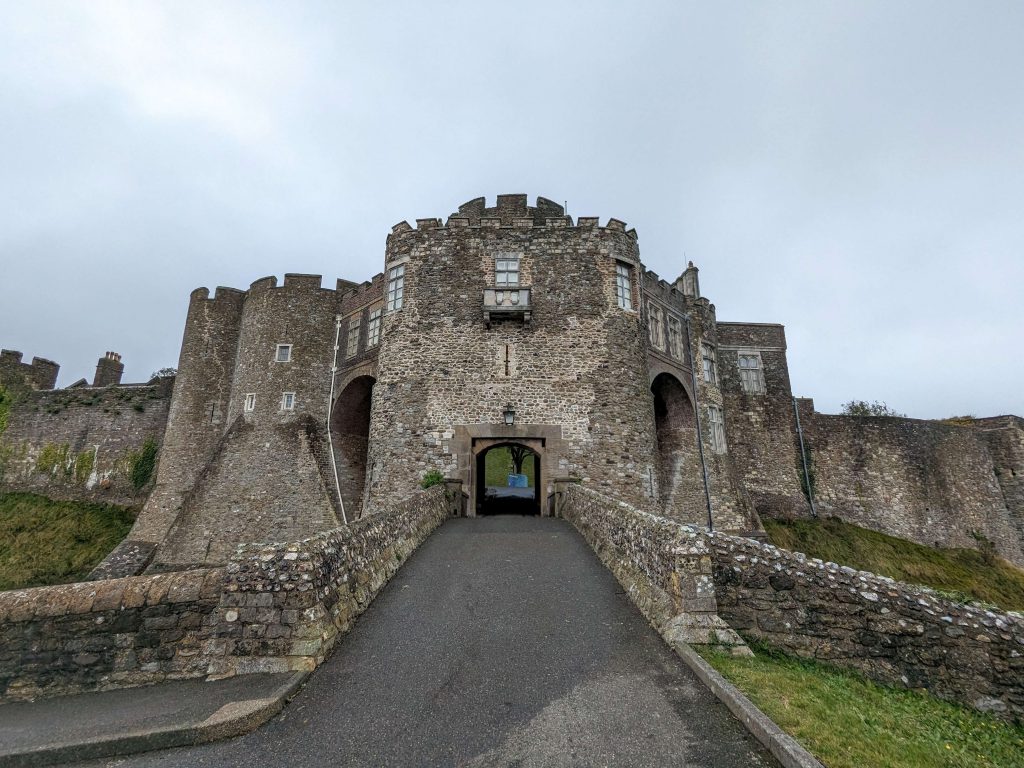

Dover Castle is a mediaeval fortress located in the Kent town of Dover, England. It is often referred to as the “Key to England” due to its strategic location on the White Cliffs of Dover, overlooking the English Channel. Throughout its history, Dover Castle has served various purposes, including military defence, royal residence, and a symbol of English strength.

| Built | 12th Century |

| Type | Concentric Medieval Castle |

| Condition | Intact |

| Ownership | English Heritage |

| Access | Public – Admission Fee |

| Postcode | CT16 1HU |

Click here to watch our video exploring Dover Castle and discover its history

Introduction

Dover Castle is a mediaeval fortress located in the Kent town of Dover, England. It is often referred to as the “Key to England” due to its strategic location on the White Cliffs of Dover, overlooking the English Channel. Throughout its history, Dover Castle has served various purposes, including military defence, royal residence, and a symbol of English strength.

Iron Age Origins

It is possible that the site where Dover Castle stands, Castle Hill, saw its first fortified settlement during the Iron Age, some time before the Roman conquest of Britain. The shape and pattern of the earthworks do not conform to what is found at typical mediaeval castle sites, but instead that of a hillfort, and hillfort construction in Britain was very prominent from 700BC up to the period of the Romans.

Roman Presence

When Julius Caesar and the Romans first landed in Britain (in Kent) in 55 BC, they knew the strategic importance of Dover, realising it as the closest point in mainland Britain to mainland Europe. After Emperor Claudius’s invasion of Britain in AD 43, the Romans built a fort at Dover which served the Roman fleet which was responsible for patrolling the eastern Channel. To guide approaching ships at night the Romans constructed two lighthouses, known as a pharos, one within the fort and one on top of Western Heights, an area of high ground just to the west. These lighthouses were octagonal, built from ragstone and amazingly the one located at the site of the castle still stands today.

Saxon Stronghold

After the Romans left Britain in AD 410, the fort at Dover transformed into a fortified Saxon town. In around AD 1000 the church of St Mary in Castro was built next to the remaining lighthouse, which was used by the church as a chapel and bell tower. The church also still stands today, but has been modified and restored over the centuries.

Norman Fortification

In 1066, William the Conqueror was victorious at the Battle of Hasting which marked the beginning of the Norman Conquest of England. William went to Dover that same year and soon saw the strategic importance of the previous Saxon settlement, and the need to rebuild and refortify the site. Although there is no evidence left today, it is likely that William ordered the construction of a wooden motte and bailey castle. It wasn’t until William’s great grandson, Henry II, became king, did we start to see the construction of a truly formidable stone fortress.

The Rebuilt Fortress (Henry II)

Henry II’s reign lasted over 35 years from 1154 to 1189, and it was in the 1180s did he order the construction of the castle that still stands today. The building of the castle was carried out by Henry’s engineer Maurice, and consisted of the inner bailey and its towers, a partial outer bailey and the huge and very impressive tower keep which stands at just over 80 feet tall. Once finished it was considered one of the most advanced castles at the time in Europe.

Henry’s main reason for this very expensive and lavish transformation wasn’t in fact for the benefit of protecting his kingdom, but instead was to restore and protect his reputation and respect after the events of the infamous murder of Thomas Becket a decade earlier.

Thomas Becket was a close friend of Henry who had appointed him Chancellor of England. When the position of Archbishop of Canterbury became vacant, Henry was very enthusiastic to appoint Becket into the role while continuing his existing role of Chancellor. Henry thought that with his close friend in this duel appointment, the Crown would be able to exercise a greater authority over the Church.

Becket did not share his friend’s ideas. He resigned his position of Chancellor and instead devoted his time and lifestyle to the Church. This caused significant tensions between the two eventually leading to Becket fleeing the country in 1164. After certain compromises were reached, Becket returned to England as Archbishop of Canterbury in 1170 to a very eager public. Tensions soon spilled over again when Becket expelled the Archbishop of York, the Bishop of Salisbury and the Bishop of London from the Church, as a result of crowning Henry’s son – a job that should have been performed by Becket.

The expulsions infuriated the trio as well as Henry. Knowing Henry’s outrage, four knights left for Canterbury to arrest Becket. Becket refused the arrest and while clinging onto a pillar in the Cathedral the knights murdered him. It was never known if Henry directly instructed the knights, but the result of Becket’s death hit hard with many people including Henry.

Becket was considered a martyr and Henry’s reputation was in tatters. Facing a considerable political crisis, a guilty Henry realised his need for repentance, eventually being reconciled with the church. Becket was made a saint by the Pope in 1173 and Canterbury Cathedral became a very important pilgrimage destination. Devoting himself to St Becket, Henry went about rebuilding Dover Castle on a huge scale during the last ten years of his reign, realising it was on the pilgrim route to Becket’s shrine in Canterbury. He poured in more money into Dover Castle than any other castle in England, with a lot of expense going into the living space. Residential rooms were decorated and furnished quite magnificently so that the castle could host important visitors making the journey.

First Barons’ War – A Castle Under Siege

Henry II never saw Dover Castle tested as a military fortress, but that would change under the rule of his son King John. During the reign of King John lands in France which included the Duchy of Normandy were lost to the French king Philip II. Hostile territory now faced Dover from the other side of the channel, so in response to this John extended the castle’s existing outer bailey, building up the outer curtain walls with towers.

On top of his military failures in France, King John was renowned for being cruel and vindictive and because of this was at odds with a group of rebellious barons who could no longer stand for his poor leadership.

In 1215 a document was issued known as the Magna Carta, which was an attempt to remedy the situation. It essentially listed a series of clauses that would preserve rights and liberties and prevent the king from exploiting his power. While the Magna Carta was agreed on by the King and Barons, commitment to abide by the clauses was not followed which resulted in warfare breaking out between the King and the rebellious Barons, known as the first Barons War of 1215 – 1217.

During the war the French Prince and heir to the French throne, Louis, was invited to England by the barons and asked to take the English crown from John. Louis agreed and joined the barons who quickly took control of several locations including London, Canterbury and Rochester. Due to its strategic importance Dover would also need to be taken, so Louis laid siege to the castle in July 1216. The castle’s garrison, led by its castellan Hurbert de Burgh, held firm and successfully repelled the attacks.

Louis didn’t give up though and the French came up with the idea of gaining entrance to the castle by tunnelling through the soft chalk rock under the foundations to weaken or collapse them, a technique known as undermining. With this they did expose the one real weakness of the castle as the French successfully brought down one of the towers of the northern gate house, allowing them to get into the outer bailey. However the strength of the garrison soon forced the French out again and some quick repairs using timber allowed the English to seal the breach.

The castle held out for three long months and by October 1216 a thwarted Louis negotiated a truce. A few days later King John died from dysentery.

Further Developments (Henry III)

After John’s death, William Marshall, 1st Earl of Pembroke, was appointed regent of England and protector of John’s nine year old son, Henry III. William asked the barons to not blame Henry for his fathers shortcomings, and slowly persuaded the barons to abandon Louis and switch sides. Fighting continued into 1217 when Louis was finally defeated at the Battle of Lincoln in May.

The new St John’s Tower located outside of the outer bailey and the rebuilt barbican was connected by an underground tunnel which also went further out to the spur. Two new gates were built to the west and east, the Constable’s Gate and the Fitzwilliam Gate respectively.

Tudors

During the era of the Tudors the castle was well maintained and utilised, as it was of particular interest to them. When Henry VIII was at the throne, the Holy Roman Emperor and King of Spain, Charles V, came to England in May 1522. Charles, who was considered one of the most powerful rulers in Europe at the time, met with Henry at Dover Castle, and during his time in England the kings formalised an agreement to invade France. As part of this arrangement it was also agreed that Charles would marry Henry’s daughter, Mary (later Mary I), when she came of age.

What transpired however was a poorly coordinated invasion which resulted in each blaming the other for not honouring their agreements. The cooperation drifted between the two which resulted in Charles abandoning the agreement to marry Mary.

Another guest of Dover Castle was Anne of Cleves after her marriage to Henry VIII. In the late 1530s to early 1540s, Henry ordered the construction of a number of artillery forts that were built in and around Dover and the South coast. Dover Castle itself was also added to, with the construction of the Moat Bulwark – the first known fixed gun position established at the castle. Strengthening the castle’s defences and to help defend the harbour, it specifically was designed to counter any threat from the sea.

The last monarch of the House of Tudor, Elizabeth I, visited Dover castle in 1573 during her travels through Kent. The Anglo-Spanish War started in 1585 and Elizabeth made sure the castle was ready for a possible attack.

Stewarts and English Civil War

The Stewards did not have the same interests in Dover Castle as the Tudors did. In June 1625, a few months after Charles I came to the throne, the French princess, Henrietta Maria, stayed at Dover Castle on her way to marry the king.

A number of alterations and renovations were made to the castle’s great tower during this time by George de Villiers, 1st Duke of Buckingham. After this however the castle went unused. It did serve an insignificant role during the English Civil War (1642 – 51) where it was initially and only briefly held by Royalist troops. Supporters of the Parliamentarians were able to capture the castle without a fight. Maybe because of this minimal involvement in the war, the castle was able to escape the slighting that so many other castles unfortunately fell to.

Napoleon

During the years around the turn of the 19th century, England was at war with France and Napoleon had his sights on Dover, establishing a huge army dedicated to the invasion of England.

Dover Castle needed to be prepared and the military engineer William Twiss was put in charge of updating the castle’s defences. Above ground the castle received a whole range of updates which included a new raised canon platform, new bastions with canons, modernisations to the spur and reinforced roofs.

Underground there were also some additions made as the castle was receiving new troops but it was already full and there was nowhere to put them. So new tunnels and underground barracks were dug out at the south side.

Another significant problem that needed to be overcome was the time it took to get troops down from the castle high up on the cliffs, down to the beach to face an invasion force. Twiss designed the ‘grand shaft’, a huge stairwell cut into the rock that went from the cliff tops down 140 feet to the bottom of them.

All of these modifications were never tested as Napoleon was never able to launch his invasion due to the Channel blockade of the Royal Navy, and by 1805 the threat had diminished.

The various tunnels and underground barracks were then left abandoned until the 20th century.

WWI

The outbreak of World War I in 1914 saw Dover and its castle play a significant role. The town had a garrison and training camps for over 10,000 men, while the castle acted as the headquarters of the military.

The Dover Patrol unit of the Royal Navy, which was responsible for patrolling the Dover Strait and to keep out enemy German shipping, used the harbour as its base of operations. To protect the town from both sea and air threats, coastal defence guns and anti-aircraft guns were installed, including some within the site of the castle.

WWII

At the start of World War II in 1939 and a new threat of invasion, Dover Castle once again played a crucial role in operations. The tunnels built during the Napoleonic wars were still secretive and were reused to home command centres for the army, navy and air force, as well as provide shelter to soldiers and civilians from bombing raids.

In 1940, from these tunnels, Vice Admiral Ramsay planned and conducted the evacuation of over 338,000 Allied soldiers from the beaches and harbour of Dunkirk, code-named Operation Dynamo.

During the subsequent years of the war two additional levels of tunnels were added. The first, called Annexe, contained space for living quarters and a hospital. The second level was a communication centre which purposely transmitted military disinformation to confound the Germans. This was key to the run up to the D-Day Normandy landings, as false transmissions were broadcast that told of Dover being the launch point of the operation.

Cold War

World War II ended and the threat of invasion had gone, but a new threat soon emerged which once again required the repurposing of Dover Castle and its tunnels. In the 1960s predominantly the lowest level of tunnels, called Dumpy, were used as one of 12 Regional Seats of Government. The purpose of these were to provide the necessary means to administer each region in the event of nuclear attack. With Dover Castle and its tunnels being situated in the chalk landscape, it was soon realised that with it being a soft, porous rock, any radioactive water from such an attack would eventually seep into the tunnels.

Modern Day

Today Dover Castle is managed by English Heritage and is open to the public .It remains a Scheduled Monument and is also a Grade I listed building.

Click below to explore Dover Castle with us