Caerphilly Castle is considered one of the most remarkable mediaeval castles in western Europe. Its exceptional features include its enormous size, the second-largest castle in Britain after Windsor, its innovative use of water for defence and being one of the first authentic concentric castles built in Britain. Constructed in the late 13th century, the castle was a revolutionary masterpiece of military planning during its time.

| Built | 13th Century |

| Type | Concentric Castle |

| Condition | Ruinous – Major Stonework Intact |

| Ownership | Cadw |

| Access | Public – Admission Fee |

| Postcode | CF83 1JD |

Click here to explore Caerphilly Castle with us and discover its history

Origins

The de Clare family, founded by Richard, had been heavily involved in the Norman invasion of 1066. As a result of this Richard was well rewarded. With lands initially focused in Kent and Suffolk, the family were considered to be one of the most powerful by the 13th century as they had also acquired both the earldoms of Hertford and Gloucester. In 1217 they inherited the lordship of Glamorgan but already by then there were confrontations with the Welsh regarding the loss of their lands. As a result of this the de Clare family had already constructed other castles (possibly including Llangynwyd and Llantrisant) within the Glamorgan area for the purpose of protecting towns.

The construction of Caerphilly Castle started in 1268 during a particularly unsettled period in the Welsh Marches. Built by Gilbert de Clare (Lord of Glamorgan, 6th Earl of Hertford & 7th Earl of Gloucester), the main purpose of the castle was to secure his newly possessed lands in Senghennydd just a few miles away from Caerphilly from any kind threat from the Welsh, who were now united under the Welsh Prince Llywelyn ap Gruffudd (Llywelyn the Last). With this threat, Gilbert wanted a fortification that was extremely strong.

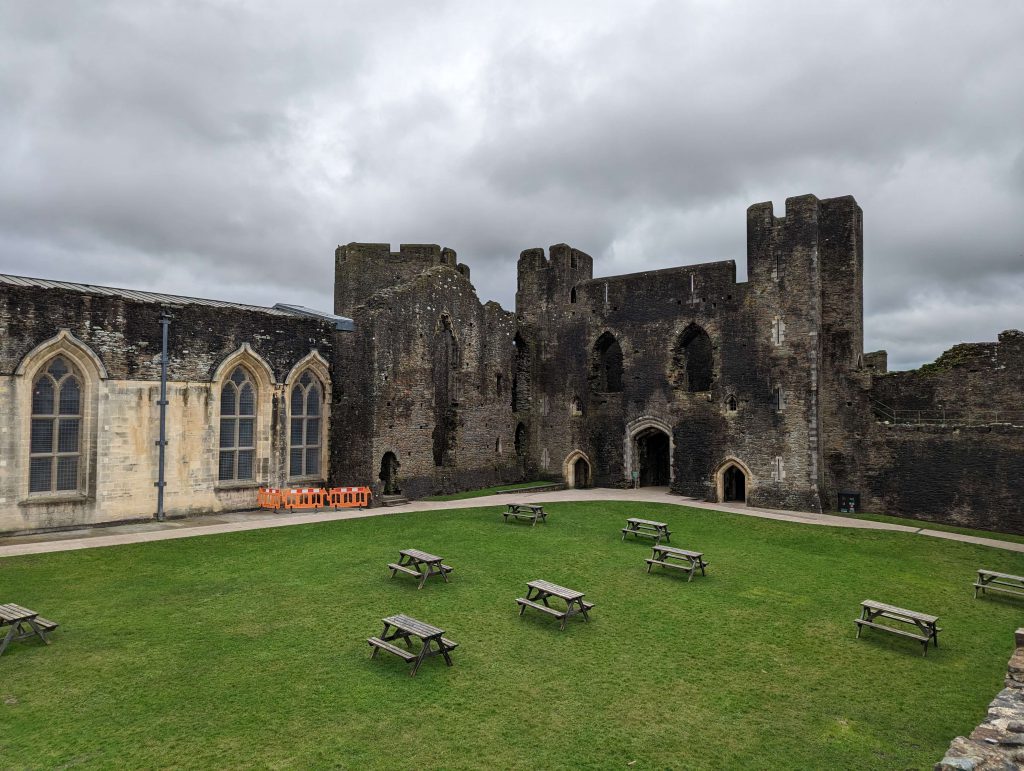

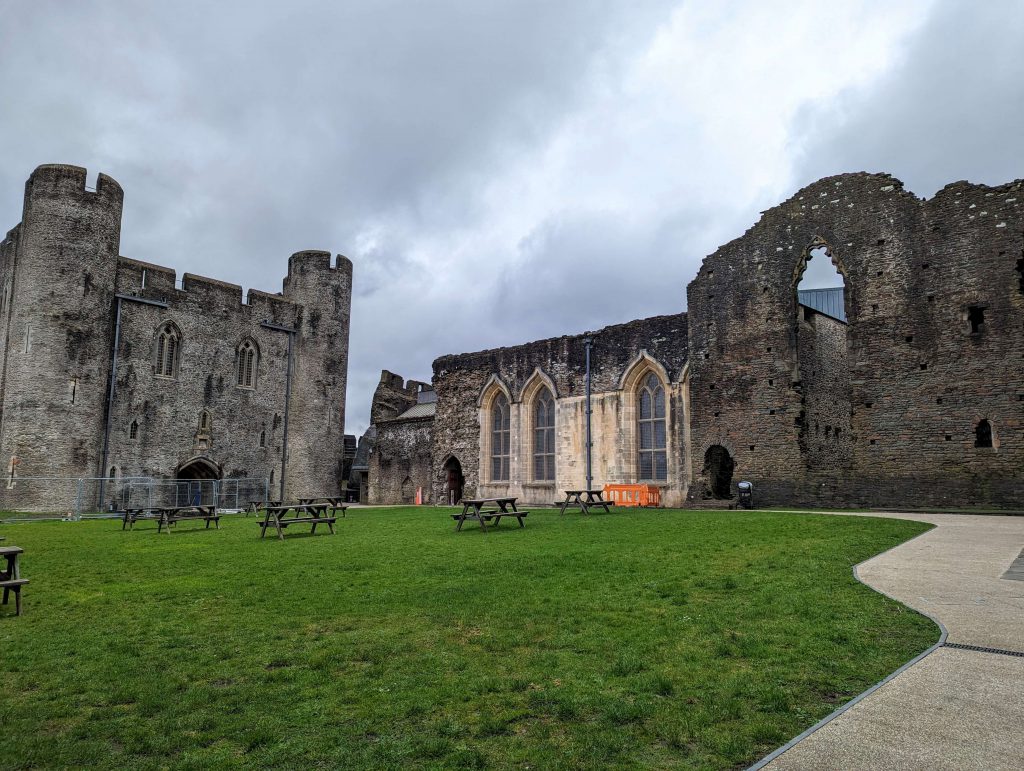

The location chosen was the site of a Roman earth and timber fort with two streams running through (Nant y Gledyr and Nant y Risca). Two enormous ditches were dug out to the north and south which formed the central and western islands. On the east side, an enormous earth platform was built which acted as a dam to one of the streams, this enclosure formed the southern lake as well as filling the moats to the north, east and west of the inner ward. With such a large area of water surrounding the castle, only the very largest of siege engines of the time would have had any kind of impact as well as making ground attacks very difficult. The islands had stone walls constructed upon them with crenellations occupied by archers.

On top of the water-based defences, the initial layout of Caerphilly was likely inspired by Kenilworth Castle. Gilbert was present at the failed siege of Kenilworth Castle in 1266 and was very impressed with the castle’s defence. The gatehouses at Caerphilly were one of the most impressive and innovative features as they controlled entry across the moats and into the inner ward, forming one of the early examples of concentric castle design.

The first test of the castle is believed to have been in 1270 when Llywelyn the Last attacked. It is highly unlikely that the castle would have been completed by this point, and it is possible that it would have been damaged, but by 1271 building work had resumed.

The castle was attacked a second time in 1294/5 but by this time the castle would have been complete. The attack was part of a series of attacks by the Welsh on various Glamorgan assets owned by the de Clare family, including the capturing and damaging of Llantrisant and Morlais Castles. The attack on Caerphilly Castle however, which was led by Morgan ap Maredudd, was unsuccessful but the town was badly damaged.

Home of the de Clare’s

As we know Caerphilly Castle was originally built as an impenetrable fortress, so by the time this first phase of construction was completed by the mid 1270s, the accommodation was not particularly extensive or inviting. There was a great hall, a chapel, service rooms, as well as a few more comfortable rooms, but these were used primarily by the castle’s garrison. There would have been some kind of space for the Earl Gilbert, but at that time, Cardiff Castle was the administrative centre for the lordship and any kind of official business or event would have been held there.

After the first phase of construction had been completed and the threat of attack from the Welsh had passed, part due to Prince Llywelyn surrendering to Edward I in 1277, modifications were made to Caerphilly to improve the castle’s hospitality. Gilbert was planning to use Caerphilly as his primary residence so began to work on modifications and additions to accommodate himself, the household and any prominent guests.

In the north west corner of the inner ward (and next to the great hall), a two story block was built consisting of private apartments. A new kitchen, a brewhouse and larder were also built to the south of the great hall. The four towers of the inner ward were also updated with more plush accommodations. This in essence transformed Caerphilly Castle from a strong fortification to more of a residence, while still retaining the majority of the actual defensive features.

The third and final phase of construction carried out by the de Clares, which was quite substantial, consisted of the outer main gatehouse with its hexagonal barbican, the north gatehouse and the north dam platform with its impressive walls and towers. This dam allowed for the large north lake to be created, enclosing the castle further with defensive waterworks.

Unfortunately it is not possible to accurately identify when these features were constructed, as the records of this phase of work were destroyed in the early 14th century when the castle was ransacked. But using the architectural style as a guide, where we have the use of polygonal shapes rather than the more traditional circular shapes, it is likely it would have been around 1280 to 1300 or even 1310, when other castles were receiving similarly shaped features. The new north dam in particular, added to the already mighty defensive qualities of the castle. Viewing the castle from the east especially really does show how massive the end product is of these three phases of work, symbolising the families power and wealth.

Unrest & Revolt

At the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Gilbert de Clare (7th Earl of Hertford and 8th Earl of Gloucester) was killed at quite a young age. He had no male heir so King Edward II took the inheritance of the de Clare family. The guardianship of Glamorgan was given to administrators that were insensitive, with violent unrest soon emerging after their appointment.

In particular Llywelyn Bren (possibly the son of Gruffudd ap Rhys), a member of the old Welsh aristocracy, was removed from his position in local office (entrusted previously by the de Clares) when Payn de Turberville was appointed as the king’s keeper of Glamorgan in 1315. The following year, Llywelyn was then ordered to appear in front of the king where he was accused of rebellious behaviour. This act proved to reach Llywelyn’s breaking point as the following day on 28th January 1316 he attacked Caerphilly, which initiated the widespread revolt in Glamorgan.

The attack came as a surprise as the castle’s keeper, William de Berkerolles, and a number of officers were captured when outside of the castle walls. Many settlements and homes were burnt or destroyed across Glamorgan, and at Llantrisant the castle was captured. At Caerphilly the outer ward sustained some damage and a drawbridge was destroyed, but the castle stood firm with a relatively small garrison under the leadership of joint heiress Eleanor de Clare, one of three sisters to Gilbert.

In March, approximately six weeks after the attack was launched, a royal army of over 2000 men was assembled at Cardiff and marched to Caerphilly for relief efforts under the command of William de Montague. On route they came across the Welsh forces stationed at Caerphilly Mountain. Montague was able to outmanoeuvre the Welsh and inflicted heavy losses. With this the army were able to get to the castle, re-garrison it with fresh troops and repair any damage that was sustained. Just a few days later Llywelyn surrendered, ending the revolt.

Payn’s tenure of Glamorgan has been quite a catastrophe and he was quickly removed from post. Llywelyn was imprisoned along with his wife and five sons in the Tower of London, and when the Lordship of Glamorgan changed two years later, and given to Hugh Despenser, Llywelyn was executed at Cardiff.

Hugh Despenser

As previously mentioned, the last earl of the de Clare family, Gilbert, died very young. He was very close to King Edward II and was extremely loyal, so his death was quite a blow to the king as he essentially lost one of his closest and most powerful allies. Eleanor de Clare, married Hugh Despenser (the younger) in 1306, son of Hugh (the elder) who was already an advisor and mentor to the king. Through this marriage Hugh, also referenced as ‘the greediest of men’ grew in stature and power himself, as he quickly acquired a 3rd of the de Clare’s estates, including the Lordship of Glamorgan in 1317. The next year he was made chamberlain of the king’s household which gave him control of the royal finances.

By 1321 many of the Marcher lords had become quite angry at Despenser’s activities. They formed together and burned or destroyed a number of his properties. Caerphilly Castle itself was captured and ransacked. Normally, the king would have backed the barons and exiled the Despensers, but instead he decided to back the Despensers, defeating the barons using loyal soldiers he had at the battle of Boroughbridge, Yorkshire in 1322.

This cemented the Despensers position, gaining influence in the kingdom as well as vast amounts of land in south Wales and the Marches. With this wealth, Hugh remodelled the great hall of Caerphilly Castle, bringing it more up-to-date with a very lavish and decorative style.

This period of ‘success’ did not last long for Hugh and also marked the start of the king’s own downfall. Edward II’s reign was considered to be quite a disastrous one with military defeats, political crisis and internal fighting. He was also quite (or probably too) reliant on Hugh Despenser who, by this time, had made many enemies. Edward II’s estranged wife, Isabella of France, had previously shown a distaste for Hugh. She’d asked the king to remove him from court, and refused to return to England after a trip to France until Hugh had been removed..

Clearly this was not going to happen, so in September 1326 Isabella landed in England with a small force and headed to London uncontested. With news of this and very little time to react, King Edward and Despenser fled west, reaching Wales in early October and eventually Caerphilly Castle by mid October. There was no local support for either in order to make any kind of defence of this pursuit, so even within the mighty walls of Caerphilly they felt the need to move on again by November. They eventually ended up in Llantrisant where they were captured by Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer.

Hugh Despenser was taken to Hereford that month where he was tried and then hung, drawn and quartered. The King was forced to relinquish the crown to his son Edward III and confined at Berkeley Castle where he was then later killed, possibly murdered in September the following year.

During all of this Caerphilly Castle had remained under siege by Isabella’s forces under the command of William, Lord Zouche. The castle’s constable, John de Felton, who was still loyal to the King and Hugh Despenser until the bitter end, successfully kept the besieging forces at bay with a garrison of 137 men. Hugh Despenser’s son and heir (also called Hugh) was also present at the castle until a surrender was eventually agreed. The garrison were all given pardons as well as the Despenser heir.

A significant amount of weapons, food and possessional wealth was discovered when the castles’ contents were catalogued, which would have been sent there by Edward II and Despenser when fleeing Isabella. The majority of the valuables would have been returned to London and back under the administration of the king’s treasurer.

Decline

After the death of Hugh Despenser in 1326, little work was carried out on the castle. Isabella briefly held the castle after the surrender, and in 1328 it was returned to Eleanor de Clare, the widow of Hugh Despenser, who had been confined to the Tower of London. In 1329 Lord Zouche (commander of Isabella’s siege of Caerphilly), abducted Eleanor and the two, without royal consent, were secretly married. The couple were arrested and king Edward III seized Eleanor’s lands. Eleanor was sent back to the Tower of London and subsequently released and pardoned in 1330, with a fine of £50,000. Lordship of Glamorgan and the castle were eventually restored back to Eleanor and her new husband.

Through the rest of the 14th century Caerphilly Castle was passed down through the descendants of Hugh Despenser and Eleanor de Clare. Towards the end of the 14th century there are records that describe repairs that were made to timbers, roofs and the storehouse.

In the early part of the 15th century, when Owain Glyndŵr led the Welsh uprising which saw many castles attacked and besieged in Glamorgan, there is little evidence to suggest Caerphilly saw much if any action. The castle continued to be held by the Glamorgan Lordships through the 15th and 16th centuries, but during the 15th century the idea of restoring the administrative centre back to Cardiff was becoming a reality with significant work being done to Cardiff Castle. Despite this, some updates were carried out to Caerphilly in 1428-29; the gatehouse was turned into a prison and the south dam saw some repairs.

Interest in Caerphilly Castle did start to flag by its owners though, and writings from the 16th century by John Leland and William Camden suggested that the castle was starting to fall into disrepair. Things got worse by the end of the 16th century, in 1593, when the castle was leased out to Thomas Lewis by Henry Herbert (earl of Pembroke). Lewis used this to take some of the stonework so that he could build his own Elizabethan mansion Y Fan, where some of the stonework taken from the great hall can still be seen today.

There are no substantial records to indicate what role Caerphilly had in the Civil War of the 1640s, if any. There is however an extensive earthworks from this period positioned to the north-west of the castle, likely built by the castle owner of the time, Philip Herbert, fourth earl of Pembroke and supporter of King Charles I. Likely built as an artillery fortification, it featured a central earthwork with a number of extruding bastions or gun positions. Either during or immediately after the civil war, Caerphilly was sadly slighted with the inner east gatehouse and the four towers of the inner ward being purposely compromised. This could well explain the quite astounding lean of the south-east tower.

Restoration

The Marquesses of Bute acquired the castle in the late half of the 18th century. It was the first marquess, John Stuart, who started to introduce measures to protect the ruins. The great hall was reroofed initially and by the time of the extremely wealthy third marquess, John Crichton-Stuart, who was engrossed by the Middle Ages, plans had been drawn up of a full restoration. It wasn’t until the 4th marquess, also called John Crichton-Stuart, was the huge task taken on. The work started in 1928 and was funded entirely by his own wealth at an estimated cost of £6.5m in today’s money. Employing 15 masons and labourers for a 12 year period, the north-east tower, inner east gatehouse, out main gatehouse and bridge, south dam and south-west tower were some of the main focuses of the restoration. At the outbreak of WWII, the restoration work was abruptly halted but did continue after, until the death of the 4th marquess in 1947.

In 1950 Caerphilly was taken into state care as the Bute family were forced to sell a lot of their south Wales property. Restoration work continues throughout the next 60 years with the repair of the two dams and re-flooding of the two lakes. Since 1984 Cadw has maintained the site and continues to carry out the restoration to this day.